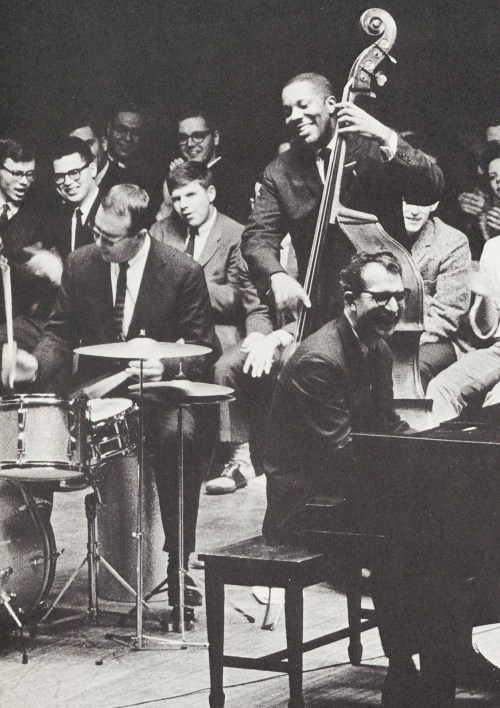

Dave Brubeck hard at work at what he does best.

“Do you think Duke Ellington didn’t listen to Debussy? Louis Armstrong loved opera, did you know that? Name me a jazz pianist who wasn’t influenced by European music!”

—Dave Brubeck

Today, I want to take a brief break from my usual Mexico posts to celebrate the 104th birthday of Dave Brubeck, a legendary jazz pianist and composer whose influence on jazz and its popularity remain as profound as the music he created.

Brubeck’s pioneering approach to rhythm, melody, and his life-long collaboration with Paul Desmond not only brought jazz to a wider audience but also cemented his legacy as one of the 20th century’s most innovative musicians.

Dave Brubeck was born in Concord, California, on December 6, 1920. He grew up with music in his veins, but initially, before fully embracing his passion for the piano, his father, Pete Brubeck, wanted him to follow in his footsteps as a cattle rancher on a 45,000-acre cattle ranch in Ione, California.

Brubeck’s mother, Elizabeth Ivey Brubeck, had a profound influence on his musical development. She was a classically trained pianist who studied under Myra Hess in London. Her background gave Brubeck his first exposure to classical music, which became a significant foundation for his jazz compositions and his later explorations of jazz-classical fusion (“third-stream”).

It was Elizabeth who encouraged Brubeck’s creativity and improvisation, especially since he struggled with reading sheet music due to his poor eyesight. This early support helped foster his distinctive approach to music, blending structured harmonies with the freedom of jazz improvisation.

His classical training, combined with a love for improvisation, laid the foundation for his groundbreaking work in jazz. Brubeck’s genius was not only in his virtuosic playing but also in his ability to compose and arrange music that pushed boundaries while remaining accessible to.

Dave Brubeck quartet: Paul Desmond, alto; Eugene Wright, bass; Joe Morello, drums; Dave Brubneck piano.

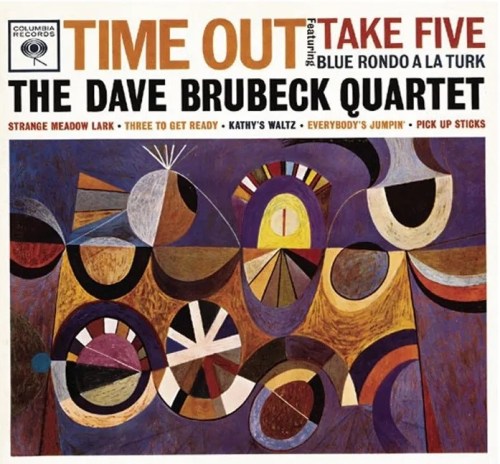

Perhaps the most iconic example of his innovation is the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s landmark 1959 album, Time Out. Interestingly, the album was originally conceived as an experiment in unusual time signatures. Time Out: The Dave Brubeck Quartet (1959). The record was a trailblazer, introducing listeners to complex time signatures that were virtually unheard of in jazz at the time. Tracks like “Blue Rondo à la Turk,” inspired by Turkish folk music, and “Take Five,” composed by his longtime collaborator and alto saxophonist Paul Desmond, became instant classics. “Take Five” especially broke ground, with its signature 5/4 time and Desmond’s silky, unforgettable saxophone melody, becoming the best-selling jazz single of all time.

Brubeck’s fascination with blending musical traditions extended beyond Time Out. He studied under the esteemed French composer Darius Milhaud at Oakland’s Mills College (financed by the GI Bill after World War II), and would often incorporate elements of classical music into his jazz compositions, aligning him with the “third stream” movement. The “third stream” movement, a term first coined by composer Gunther Schuller, sought to merge the improvisational freedom of jazz with the structural intricacy of classical music, and found a natural ally in Brubeck’s adventurous spirit. Works like “Blue Rondo à la Turk” highlight his ability to seamlessly weave disparate musical traditions, creating a sound that defied easy categorization and brought jazz into dialogue with classical idioms.

Time Out was revolutionary not just for its technical complexity but also for its commercial success. Jazz, often seen as niche, was catapulted into the mainstream, reaching audiences far beyond its traditional fan base. Brubeck’s ability to bridge this gap between sophistication and mass appeal made him a cultural icon, demonstrating that jazz could evolve without losing its heart. But beyond the album’s technical complexity, this was just very listenable music.

Central to Brubeck’s success was his extraordinary partnership with his alto sax player Paul Desmond. Their creative synergy was palpable, producing a sound that was both adventurous and harmonious. While Brubeck’s piano often delivered bold, rhythmic innovations, Desmond’s saxophone brought a contrasting elegance and lyricism. Together, they formed a “call and response” dialogue in music that captured the essence of jazz improvisation: spontaneity, emotion, and interplay.

Beyond the music itself, Brubeck was steadfast in his commitment to civil rights, notably refusing to perform at segregated venues in the South. A clear example of this occurred in 1957 when Brubeck and his quartet canceled a performance at the State Fair Park auditorium in Dallas, Texas. This venue was known to enforce segregation, and while, unfortunately, Brubeck did not publicly articulate his reasons at the time, reports indicate that his decision was directly related to the auditorium’s discriminatory policies. A fan letter from Betty Jean Furgerson, a Black woman, later thanked Brubeck for his stance, noting his quiet yet significant protest against segregation:

All this is to thank you for acting like a decent, feeling human being. You can never know how much it means to me to know that there are people [who] react positively to injustices. Too many of us give lip service to it. It’s much easier and less convenient and more comfortable. It is a terrible thing to have to deny people the beauty of your music because they fear unintelligently.(Furgerson letter to Brubeck, qtd. in Klotz)

Bassist Eugene Wright clearly having a good time playing with the quartet at a college in the fifties.

This was not an isolated incident. Brubeck also famously canceled a $40,000 tour of the South in the early 1960s because one of the tour’s sponsors demanded that his integrated band replace bassist Eugene Wright, who was Black, with a white musician. Brubeck’s refusal underscored his unwavering principles and his commitment to equality, even at significant financial cost (Klotz).

It’s clear that Brubeck used his influence to challenge racial injustice. His actions reflect the broader ethos of jazz during this period as a medium for improvisation and inclusivity that defines jazz itself.

As a side note, Brubeck tells the story about an encounter he had as a child with an elderly Black cowboy—an encounter that deeply influenced his views on race and humanity. In Philip Clark’s biography of Dave Brubeck, Brubeck recalls the incident vividly, sharing how his father took him to meet a neighbor who, as a former enslaved person, bore the scars of branding on his chest. This story is not only a pivotal personal moment for Brubeck but also illustrates how he channeled these experiences into his music and activism.

The following is a short youtube clip from the Ken Burns PBS series Jazz, where Brubeck describes this encounter in very emotional terms.

Brubeck’s career spanned over six decades, during which he continued to compose and perform, inspiring generations of musicians and listeners alike. His work demonstrated that jazz is not just a genre but an ever-evolving art form, capable of breaking down barriers and connecting people through rhythm and soul.

So, on what would have been his 104th birthday, we honor Dave Brubeck not just as a musician but as a visionary, a composer, and an activist. His contributions to jazz, from Time Out to his adventurous compositions and his unwavering commitment to collaboration, remind us why his music continues to resonate today. As we listen to the timeless strains of “Take Five” or the exhilarating rhythms of “Blue Rondo à la Turk,” we celebrate a life well-lived and a legacy that will endure for generations.

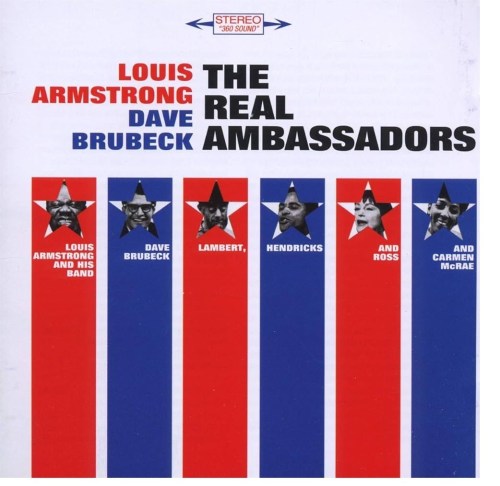

“The Real Ambassadors”: Back row, L-R: Howard Brubeck, Danny Barcelona, Eugene Wright, Joe Morello, Billy Cronk, Dave Lambert, Yolande Bavan, Jon Hendricks and Iola Brubeck; front row, L-R: Trummy Young, Carmen McRae, Louis Armstrong and Dave Brubeck. Rehearsal at St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco for performance at Monterey Jazz Festival 1963. from Brubeck Collection

For first-time listeners, here are five essential Dave Brubeck albums that showcase his versatility, creativity, and contributions to jazz:

Time Out (1959)

This groundbreaking album is Brubeck’s most famous work and a jazz milestone. It features innovative time signatures, including the iconic “Take Five” (in 5/4 time) and “Blue Rondo à la Turk” (in 9/8). Time Out broke barriers by bringing complex jazz to a broader audience, becoming the first jazz album to sell over a million copies.

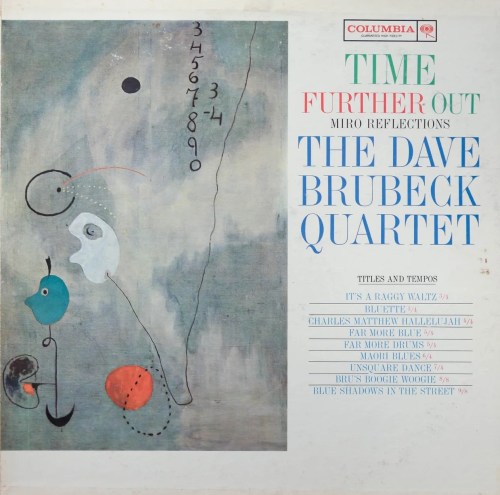

Time Further Out (1961)

A sequel to Time Out, this album delves deeper into unconventional rhythms and includes the track “Unsquare Dance” (in 7/4). It extends Brubeck’s exploration of time signatures while retaining his melodic, accessible style. The cover art, featuring Paul Klee, mirrors its avant-garde musical approach.

Jazz at Oberlin (1953)

One of Brubeck’s early live recordings, Jazz at Oberlin, captures the raw energy of the Dave Brubeck Quartet during a pivotal moment for jazz in college settings. It helped establish Brubeck’s reputation as a leading figure in West Coast jazz and includes vibrant renditions of standards like “Stardust” and “These Foolish Things”.

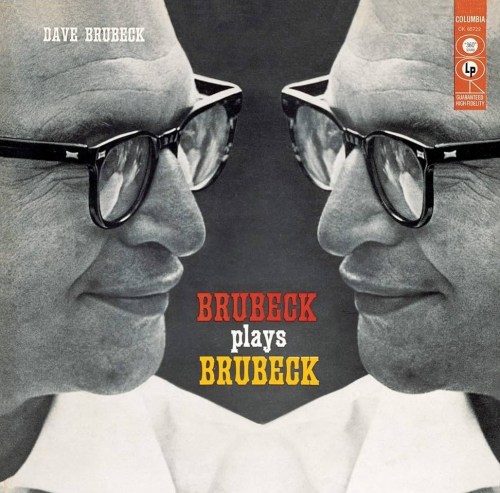

Brubeck Plays Brubeck (1956)

This solo piano album offers an intimate look at Brubeck’s abilities as a composer and pianist. Featuring pieces like “In Your Own Sweet Way”, it highlights his classical influences and innovative approach to harmony and improvisation.

The Real Ambassadors (1962)

A collaboration with Louis Armstrong and Carmen McRae, this concept album addresses civil rights and cultural diplomacy through jazz. Tracks like “They Say I Look Like God” blend poignant lyrics with powerful performances. It’s a unique and socially conscious piece that reflects Brubeck’s advocacy for equality. (See photo above)

These albums span the breadth of Brubeck’s career, capturing his pioneering spirit and his ability to combine complexity with accessibility.

Sources:

Brubeck, Chris. “My Mentor, My Collaborator, My Father: Dave Brubeck.” Newmusicusa.org 19 Dec. 2012 https://newmusicusa.org/nmbx/my-mentor-my-collaborator-my-father-dave-brubeck/

“Dave Brubeck: A Master of Jazz Across the Ages.” Themusicalheritagesociety.com 23 July 2024 https://themusicalheritagesociety.com/blogs/news/dave-brubeck-a-master-of-jazz-across-the-ages

“Django, by the Modern Jazz Quartet.” The Music Aficionado. 19 March 2018 https://musicaficionado.blog/ 2016/03/19/django-by-the-modern-jazz-quartet/.

Third Stream.” Jazz Music Archive. https://www.jazzmusicarchives.com/subgenre/third-stream

For more on Brubeck’s refusal to refusal to replace black bassist Eugene Wright, see

Klotz, Kelsey A. K. “Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy.” Spring 2019 Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences https://www.amacad.org/sites/default/files/publication/downloads/05%20Klotz.pdf

For more from the “third stream” genre, listen to the Modern Jazz Quartet, Django:

The Modern Jazz Quartet’s Django is a groundbreaking album that exemplifies the “Third Stream” movement, blending jazz improvisation with classical compositional techniques. The title track is a tribute to Django Reinhardt, and is essentially a blues, but “owes as much to Bach as it does to the blues,” marked by its “somber melody” and intricate counterpoint (“Django”). Led by John Lewis on piano and Milt Jackson on vibraphone, the album is an exercise in fusing the elements of blues with the baroque, creating a highly listenable emotional soundscape.