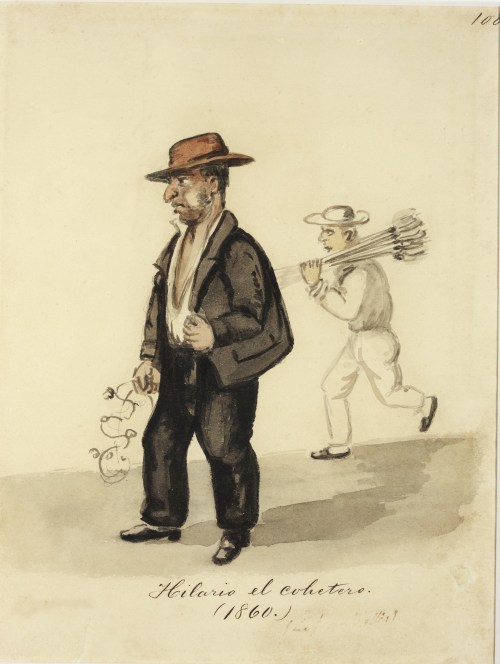

“Hillario el Cohetero,” holding fuse, with bombas coheteros background, water color by Pancho Fierro, 1866, public domain

It’s 5:00 AM in Ajijic, Mexico, and again this morning, right on time, someone in the street in front of the our Airbnb sets off a huge bomba (also known as bombas cohetes or rocket bombs). It will be the first of several loud, jarring blasts that will break the morning calm.

The “someone” responsible is the local neighborhood cohetero—a specialist whose job is to light the fuses of these mostly handmade cohetes. Though I’m no expert, judging from the sheer precision and timing of each thunderous blast hint at his skill. No need to worry; our host assures us that a life-time of practice has made our local cohete an expert in the fine art of fuegos artificiales artesanales, or Mexican artisanal fireworks, likely crafting and setting them off since childhood. If volume and timing are any measure, he’s truly a master cohetero.

Jorge Ballinas Constantino, master cohetero of Socoltengo, Chiapas, MX, readying bombas cohetes.

However, despite the cohetero’s expertise, his early-morning displays are anything but subtle. Most expats find it can be impossible to sleep through the nerve-wracking noise. Even though Jackie and I have experienced them before on each of our previous Mexico journeys, we never get used to them. To the uninitiated, the sound of the bomba is sudden, nerve-wracking, and, at times, a bit frightening.

For example, our host told me one morning several guests had inquired about the source of the deafening pre-dawn pop, pop sounds. They wanted to know why there was a “war” going on in the streets? They mistook the sounds as gunfire and were genuinely shaken by the prospect of a gang war going on in the street outside our Airbnb. I can’t blame them for their reaction. I couldn’t tell the difference between the sound of an exploding cohete and the sound of a handgun. One thing is for sure—once your nerves have been rattled by a choete, you’ll never forget it. But then, that’s the point.

For the duration of our stay here at La Victoria, these early-morning bombas are a daily occurrence. Even when I know to expect them, it’s impossible not to start. My North American sensibilities make me dislike the relentless blasts, yet I recognize they’ve long been woven into Mexico’s cultural traditions and religious beliefs, and are an inescapable part of Mexico’s daily life. And that’s a good thing. Because it’s impossible for us to escape the fireworks, I’ve learned it’s best, at the least, to try to understand how and why these fuegos artificiales are so deeply woven into Mexican culture.

Parroquia de San Andrés Apóstol in el centro Ajijic, MX. Originally built in the 16th century, during the Spanish colonial period.

This particular morning, because of their regularity, it’s clear the explosions act as a kind of Mexican alarm clock, ticking off each quarter hour to summon families in our local barrio, or neighborhood, to mass. Meanwhile, in between the explosions, I can hear the faint pealing of the bells from Parroquia de San Andrés Apóstol ringing in the distance, marking the church’s own version of the time.

In Catholic Mexico, bombas are often used as part of religious celebrations, such as patron saint festivals. Here in Ajijic, the Feast of San Sebastián, patron saint of farmers, soldiers, and athletes, is celebrated in late January. The tradition stems from the belief that bombas, could draw God’s attention or even the attention of saints. The intense expressions of the sounds, light, and fire could communicate reverence, gratitude, or requests for divine favor. The noise was often seen as a way to “announce” a special event, invoke blessings, or ask for protection or assistance. Historically, bombas have long been used to ward off any evil spirits lingering in the pre-dawn streets—spirits that might hope to lure some early morning citizen into sin and malefaction.

And another cohete explodes, marking the time at 5:15 AM.

What we expats must recognize, if we are to live in this remarkable country, is that these celebrations aren’t just about making noise for the amusement of thrill-seekers—they hold deeper cultureal significance.

The reality is that these celebrations stem from ancient rituals rooted in Mesoamerican and Aztec religion. The Aztecs, for example, had a profound reverence for fire. They saw fire as a powerful and purifying force. Fire had restorative powers, burning away the old to make way for the new.

A model of what the Aztec “death whistle” looked like. From Mexicolore

The Aztecs performed fire rituals to honor their gods, with sacred fires kept burning in temples. Loud sounds, from “death” whistles to drums, were central to indigenous ceremonies—not only as a means of reaching the gods but as a way to repel negative forces or evil spirits.

The unavoidable truth about Mexican life is that no celebration—religious or otherwise—is complete without an attending barrage of exploding cohetes, towering castillos with dazzling displays of colorful, spinning fireworks (fuegos artificiales), thunderous drums, and brass bands, blaring out a mix of música de banda and danzón. This blending of traditions, known as syncretism, is evident in every celebration, where ancient Mesoamerican practices meet Catholic influences in a vibrant and meaningful expression of Mexican identity.

Today’s version of these rituals is drawn from Mexico’s ancient past while also gaining the approval of the church—a unique fusion of Catholicism and indigenous tradition. This blending of old and new reflects a cultural resilience, where traditions have evolved yet remain a meaningful expression of local beliefs. For those of us who are new to this country, understanding these rituals as both an echo of ancient ways and a living part of modern life can help us appreciate the depth and significance behind the sounds that fill the air. And in that fusion of sacred and secular, of old and new, we see not only the heart of Mexican culture but a reminder of the enduring human impulse to honor both our history and our present.

For further reading:

—On the blending of the sacred and the secular (syncretism):

“Colonial Mexican Syncretism: The Fusion of Indigenous and Catholic Beliefs” from Mexicohistory, https://www.mexicohistorico.com/paginas/Colonial-Mexican-Syncretism–The-Fusion-of-Indigenous-and-Catholic-Beliefs.html.

Megalee. “Mexican Catholicism: A Syncretism of Christianity and Indigenous Faiths.” Magalee’s Latin American Studies 201 Blog, 23 February 2021, https://blogs.ubc.ca/magamagica77/2021/02/23/mexico-catholicism-a-syncretism-of-christianity-and-indigenous-faiths/.

Frankovich, Jessica. “Mexican Catholicism: Conquest, Faith, and Resistance.” Berkley Center, 22 March 2019, https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/posts/mexican-catholicism-conquest-faith-and-resistance.

—Use of fire in Aztec rituals:

“The Sacred Fire: Symbolism in Aztec Rituals.” Aztec Mythology World Wide, https://aztec.mythologyworldwide.com/the-sacred-fire-symbolism-in-aztec-rituals/.

Scherer, Andrew K. “Fire in Mesoamerican Ritual.” Mexicolore, 28 Jan. 2021, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/home/fire-in-mesoamerican-ritual#:~:text=Among%20the%20Aztec%2C%20this%20was,make%20way%20for%20the%20new.

—Interesting article about Aztec “Death Whistle”:

Cabrera, Roberto Velázquez. “The ‘Death Whistle.’” Mexicolore, 18 Sept. 2011, https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/music/death-whistle.